If you're a fan of textile art, you might be looking for a new tapestry to complement your home decor.

But where did this art form come from? What is the history of tapestry?

What is Tapestry?

Tapestry is one of the oldest forms of woven textiles.

Typically, tapestries are made by a loom, creating a thick, textured textile fabric where weft, or horizontal, threads are woven into vertical (warp) threads to create intricate pictures and designs.

When each weft thread has been woven all the way across all the warp threads, the weft is then pushed down firmly.

Row after row of weft threads build until the warp is entirely hidden. The finer the weft threads, the closer together they sit, and the more detailed the design on the resulting cloth can be.

Tapestry weaving is a painstaking art that takes years to learn and a lifetime to perfect. Like many handcrafts in this day and age, the art of weaving tapestries is dying out, and mass-produced machine processes are taking over the art form.

Though for many years, artists wove their designs entirely from their minds, in the middle ages, weavers began using a guide called the cartoon.

This guide was a picture of the desired tapestry design that was placed behind the warp threads, allowing the weaver to follow along as she chose yarns and colors for each additional weft.

Weavers created tapestries on one of two kinds of looms: high-warp or low-warp looms. The high-warp loom is what you probably think of when you imagine a loom.

It stands vertically, and the warp threads are stretched vertically from the bottom to the top of the frame. The linen, wool, or cotton threads are strung in two groups, separated by a rod which puts one set of threads in back and one in front.

The sets of warp thread can be shifted, with the front set moving backwards and the back set moving forwards, in between each pass of weft threads.

On a low-warp loom, the warp threads are strung horizontally. Similarly to the high-warp loom, the warp threads on the low-warp loom are divided into two groups.

The shifting of the threads is accomplished by a foot-motion pedal on a low-warp loom.

Since the weaver can use both hands and feet to weave, weaving on a low-warp loom is a much faster process than weaving on a high-warp loom.

Tapestries were woven on both types of looms since the earliest-known history of tapestries.

The Latin name for tapestry (tapetium) is taken from the Greek.

The earliest written records of woven cloth appear in the Bible (specifically Chapter 26 of Exodus). Some believe that this cloth was a tapestry.

The first-known tapestries were created in ancient Egypt.

Tapestry fragments were found in the tomb of the Pharaoh Thutmose IV. Depictions of an early frame loom were found on pottery uncovered by an archaeological party, as well as painted on the walls of the tomb of Beni Hasan in Egypt.

This painting is thought to have been created c. 3000 BC and it clearly depicts workers on a tapestry-type loom.

Archaeologists have also found evidence that tapestries were woven by the ancient Hebrews, Greeks, Romans, Chinese and the Incas.

Vase illustrations by the Greeks dating back to circa 500 BC also show women weavers working at looms.

Evidence of tiled and mosaic floors would suggest that their works of art were wall hangings, not carpets, and were used as such before rugs were commonly employed to adorn the floor.

The Romans also valued tapestry and, although they did not appear to have woven tapestries themselves, there is some evidence that they traded to obtain woven textiles with the Egyptians, Persians, Babylonians, and Indians.

So ancient peoples were well aware of the way in which tapestry wall hangings can beautify a home. As well as being used for decoration and insulation, tapestries were also used to bury the dead in ancient Egypt and in the Incan civilization.

The ancient Greeks used tapestries to decorate the walls of their important government buildings.

The history of tapestry can be traced from these ancient civilizations to Middle Ages Europe, where the most famous tapestries ever created where born.

Once the art form took hold, European weavers held on to the craft, churning out warp and weft textiles for centuries.

Despite their early beginnings in Greece, the West's use of tapestries petered out and there was a dry spell until the 8th century when the Moors came to Spain.

The industry reignited, spreading to France where the art flourished.

Perhaps the most famous spot for tapestry weaving was Flanders, which was blessed with ideal conditions for tapestry creation.

Ample plants to create a range of dyestuffs were found in the region, which was close enough to England for easy access to premium wool. Additionally, the area was blessed with an abundant water source.

Gradually, Flanders became the center of tapestry weaving and its dominance lasted about 300 years. Tapestry weavers were also found in Ghent, Bruges, Ypres, and Valenciennes.

In the 1200s and 1300s, the Catholic Church realized that tapestries woven with scenes from the Bible could help transmit the word of God to illiterate church-goers.

Many were made, often in sets, or series, but only a few have survived. The oldest existing series of church tapestries is the Apocalypse of St. John.

These six tapestries measure a staggering 20 feet high, and hung next to one another, span an incredible 468 feet.

Experts estimate that they took between 50- and 84 man-years of work by the weaving team, who wove them in Paris over the course of five years in the late 14th century, commissioned by Louis 1, the Duke of Anjou. (Paris was the epicenter of the European tapestry industry until the Hundred Years War prompted weavers to flee to what is now Belgium and northern France.)

The Apocalypse tapestries were lost in the late 18th century, but were eventually found and rehabilitated. They are the oldest medieval French tapestries that still survive, and currently are housed at the Musée de la Tapisserie, Château d'Angers, Angers.

In the Middle Ages, tapestries became a measure of a person's wealth and prestige.

Some aristocrats were so attached to their tapestries that they actually took them with them when they went visiting, as a visual reminder of their status in society.

Aside from this, tapestries were used for practical purposes, such as to insulate drafty castle walls or cover windows.

To the victor went the spoils, and tapestries were no exception - those who were defeated in battle often had their tapestries plundered.

If the tapestry did not fit in the conqueror's home, it might be cut up or otherwise altered to fit.

More recently, the kilim rug has been made by Middle Eastern weavers. Though kilims are usually used as rugs to adorn a floor, they are indeed a form of tapestry.

Despite the prestige associated with owning tapestries, the actual weavers were not an affluent group.

They were often itinerant craftsmen who traveled from town to town, peddling their skill, which usually stayed in the family as the art was passed down from parent to child.

It might take a two-man weaving team two months just to produce one square foot of intricate textile.

One popular pattern was the mille fleurs (translation: thousand flowers), which was a painstakingly achieved background made up of hundreds of small flowers.

Some historians believe that this design was inspired by the flowers that locals would scatter on streets during feast day celebrations.

Of course, medieval weavers couldn't just go buy yarns in the colors they needed. Each color of thread needed to be created by hand.

And in the era before synthetic dyes, the dyes themselves had to be made from plants and insects. Madder wood yielded red dye, as did pomegranates.

Woad produced blue, and snails were boiled to make purple.

In addition to Bible stories, medieval tapestries often depicted popular legend or myths, symbols and scenes from daily life - both common (serfs working on an estate) and aristocratic (nobles astride horses on the hunt).

Victorious monarchs ordered tapestries to be created depicting their victories in battles.

In one extreme case, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V brought along an artist who sketched him in battle.

These sketches were later used as cartoons to weave tapestry depicting his glorious conquest.

Tapestries of verdant green nature scenes, known as "verdure," later became popular, and by the 1500s, they were considered a tapestry form unto themselves.

Featuring largely green coloring and intricate patterns of plants and flowers, later they began to include some animals as well.

With the rise of the cartoon in medieval times came less creativity and resulting variance in tapestries produced.

By the time of the Renaissance, weavers began to adhere to the cartoons more strictly, and less variety was seen overall.

Many tapestries were made that were copies of famous paintings.

Perhaps one of the most famous tapestry commissions was awarded to Raphael.

In 1515, the pope employed him to paint cartoons for the Acts of the Apostles tapestries destined for the Sistine Chapel.

About a century and a half later, tapestry factories began popping up.

Louis XIV's reign in France was punctuated by the opening of the Les Gobelins factory in Paris.

More than 800 weavers found work in this tapestry production factory, and they were not the only ones. Factories popped up in other countries in Europe, often sponsored by the countries' rulers, who were eager to see the art flourish in their territories.

Flemish tapestry weavers, by this time known as some of the most skilled in the world, were sought after to staff the factories. The Flemish workers had to apprentice for 12 years before being let loose on a loom.

Tapestry collection became a popular royal past time. When King Louis XIV died, 2,155 tapestries were recorded in his estate.

The bloody Henry VIII owned more than 2,000 tapestries, which were housed in 17 of his homes.

Tapestry artist Francois Boucher worked in France in the 18th century.

Boucher served as director of the royal workshops at Beauvais as well as art director of the Gobelins factory in Paris, and designed cartoons that were used in the creation of more than 400 tapestries.

This artist is considered one of the greatest tapestry designers in world history. His favorite themes were mythology and women - bordering on the erotic.

The French Revolution disrupted not only French society and the course of the country's history, but the history of tapestries as well.

In the pursuit of freedom, equality and brotherhood, the revolutionaries had no use for the aristocratic nuances of tapestry.

The social changes were never more starkly evident than when 190 tapestries were burnt in 1797, rather than be preserved for their historical and cultural value.

The gold and silver that would be recovered after melting down the rest of the tapestries, was considered to be of more use than the pieces' historical connotations.

The decline of tapestry as an artform and resulting dissipation of the skill set can be traced from this time.

It was very soon after the revolution, that the first industrial modifications to the tapestry industry, the first improvements that would automate the process, were introduced.

Jacquard

Joseph-Marie Jacquard was a tapestry weaver who was born in France before the revolution.

His father taught him to weave when he was just a child.

As the French system of life and tapestry industry collapsed around him, Jacquard began building a new, better, loom that would allow weavers to create tapestries more quickly.

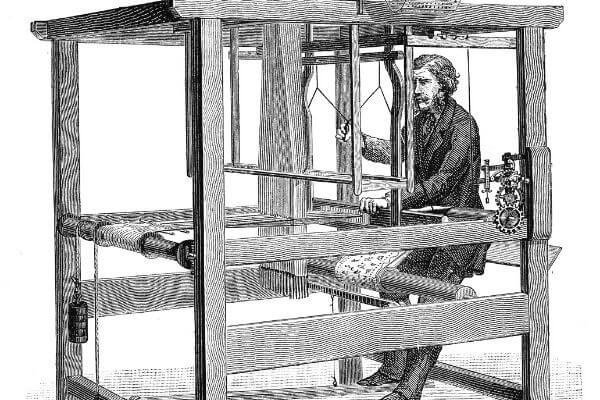

This loom was later named after him and is known as the Jacquard loom.

The Jacquard loom is mechanical. It automates and standardizes weaving, replacing hand movements with cards that have holes punched in them.

The cards control the pattern and can be used over and over again to create copies of tapestries.

Incredibly, the Jacquard loom is actually credited as being the precursor to mathematician Charles Babbages' Analytical Engine, popularly considered to be the first computer, though it was developed in the 1800s.

The Jacquard loom is such an enduring piece of equipment, that it has barely changed since he invented it, and is still used today.

William Morris

William Morris, who lived in England in the 19th century, was a famous textile designer, but he was also a writer and artist.

He started a design company with two other artists. This company did not make tapestries alone - it focused on textile design and wallpaper.

But William Morris rose to become a famous name in tapestries, with the resurgence of the art form in modern times credited to him.

Morris greatly respected tapestry weaving, even going so far as to call it "the noblest of the weaving arts."

He wove the Acanthus and Vine tapestry, his first, in 1879. This tapestry was inspired by the verdure style, and he wove it on a traditional high-warp loom, despite the fact that Jacquard looms had been widely used for nearly a century by this point.

A traditionalist, Morris insisted on using the most traditional methods, and he wove on that loom for more than 500 hours to complete his wool and silk masterpiece.

Morris continued to weave tapestries until his death, and established a tapestry weaving industry in his business that employed nine weavers working on three looms.

Though Morris successfully revived and taught himself traditional tapestry weaving methods, the fact is that no one is hand weaving tapestries today.

As is the case throughout history, technology has taken over and today's tapestries, with few exceptions, are mass-produced by automated machine processes.

Contemporary tapestries are affordable and cheap - many textiles that are called tapestries are simply pieces of cloth that are printed with a design.

Even tapestries that are woven are created by machine.

But despite the fact that machines are used, there are still many processes that must be completed in production.

Cartoons are still used today, but they are read by machine instead of by human weavers.

The design must be translated to the cartoon and Jacquard punch cards must be made - thousands of them for a single tapestry.

Computers help, but a person still has to be involved in the process. Yarn colors must be matched and the loom must be threaded.

Weavers don't physically pass the shuttles between the warp strands by hand anymore, but they still must supervise the machine process.

The Differences

Many textiles sold as tapestries today are not actually tapestry.

They are just designs or scenes printed onto a piece of fabric. A textile really must be woven in order to properly bear the name of tapestry. Do not confuse tapestry with embroidery, where a needle and threads are used to stitch a design onto the surface of fabric, nor with appliqué, where pieces of fabric are sewn onto a cloth background.

To make things confusing, one very famous textile that has the word "tapestry" in its name is not actually a tapestry at all, but an enormous piece of embroidery.

The Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidered cloth that is 230 feet long and 20 inches tall.

It tells the story of the events leading up to William the Conqueror's famous 1066 invasion of England.

Though it appears to narrate from the point of view of the conquering Normans, historians agree that it was actually made in England sometime in the 11th century.

It is thought that it was commissioned by Bishop Odo, the half-brother of William the Conqueror, though it was rumored in legend that Queen Matilda, William's wife, and her ladies-in-waiting actually embroidered it.

The Bayeux Tapestry is not tapestry.

It consists of 72 different scenes embroidered onto the cloth.

True tapestries have been woven since, reproducing some of the individual scenes.

In a sense, the piece of embroidery was the original while the tapestries woven from it are the copies.

Tapestries were copied through the use of cartoons (a drawing or painting). In early times, cartoons were not very detailed, sometimes just a quick sketch of the design.

This allowed workers more creativity in realizing the design; they could put more of their own personality into it.

Later, cartoons evolved to be far more intricate, with great detail in both color and design so that weavers could faithfully interpret the pattern with minimal variations.

In many parts of Europe, and in ancient Greece, weaving tapestry on a loom was a women's job.

Greek women told their cultures' stories through their art, much like a painter would. Some early Greek tapestries depicted mortal women and goddesses, including Athena, Aphrodite, and Queen Penelope.

One popular story told in tapestry was that of the fates - or three witches.

In Greek myth, the fates quite literally could cut the thread joining a person's soul to this life, and cause them to pass into the next world.

There are countless famous tapestries in history. Here are some of them:

My Final Thoughts

We hope you've enjoyed this journey through tapestry designs, starting in ancient times and continuing into 20th century tapestries.

As you can see, European tapestries produced by artisans have been the most enduring, with their designs and work gracing the world's most prestigious museums.

There are many modern-day tapestry producers as well, most using automated, modern techniques. If you are interested in tapestry decor for your own home, check out our shop.

We have a range of tapestry designs to suit any style or room in your home.

(Of course, if you were paying attention while you read this article, you'd know that our tapestr